I launched y.gy a few

months ago as a next-generation link shortener. This came out of

a personal need: my other project, getwaitlist.com , uses lots of referral links, and I wasn't convinced by any of

the other link-shortening solutions out there. So I thought I

would make my own, and perhaps it'd be useful to other folks

like me.

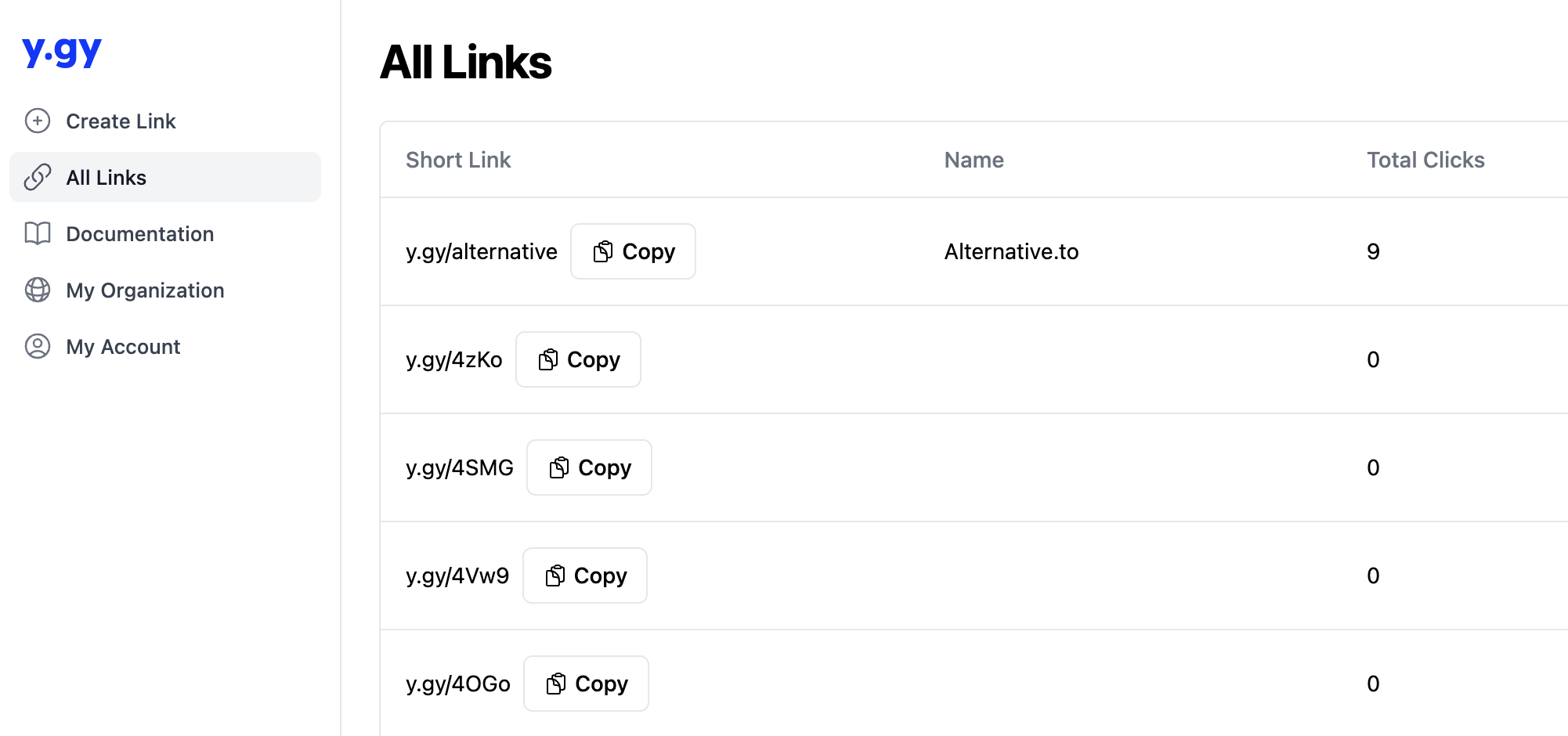

I built a best-in-class link shortener with all the bells and

whistles: from extensive customization to really good traffic

analytics. It was everything I needed. As for many other link

shorteners, I put the "Shorten Link" interface front-and-center

on the home page, no signup required. I made usage free and

unlimited, figuring that

free is always the best marketing strategy. I quietly

released it and began promoting it. I quietly

released it and began promoting it.

Scams from Day One

Malware came on day one. Some of the very earliest links that

were submitted were obviously phishing

links: fake login pages for Microsoft Online, made in free

website builders. It dawned on me that of all the people most

incentivized to find new free link shorteners are cybercriminals

who keep getting banned from the other ones! They need link

shorteners to obscure their traffic and make it harder to block

their malicious pages.

I tried submitting some of those same links to other free link

shorteners like Bitly and TinyURL to see how they were dealing

with them. It became clear reasonably quickly that they had some

internal blacklists that disqualified certain domains or types

of websites, while other malicious sites were getting through. I

reasoned that I would just have to keep an eye on it myself.

People were usually submitting fewer than 100 links a day, so it

was pretty easy for me to take 20 minutes and quickly check them

out. I made a basic dashboard for monitoring the links that were

getting submitted, and then could mark them as legitimate or

banned.

Trustworthiness at the Domain Level

Many of the links were always on the same domains, so I created

some whitelisting and blacklisting logic. For example, a

https://youtube.com/ link is always going to be

legit. On the other hand, I could see that certain domains were

always a scam. I remember a domain like

my-online-store.shop where each subdomain like

etsy.my-online-store.shop or shopify.my-online-store.shop would then be a

separate phishing link. Cybercriminals have lots of domains, but

not infinitely many (they do cost money!), so banning at the

domain-level was actually quite effective.Ironically, I soon noticed that an easy way for criminals to get

around domain-bans was to use other link shorteners to disguise

their link (much in the same way that they were trying to use

y.gy). There was an easy fix there: I compiled an open-source

repository of link shortening URLs

and added them to the auto-ban blacklist.

A big problem that came up at the domain level was what I'd call

a trustworthy domain with untrustworthy subdomains

, specifically where those subdomains represent user-generated

content. I noticed that Hubside, Wix and Replit were

frequently abused because of their generous free plans and

seemingly lax security. Sometimes I'd wake up to 500 new links

all from one

subdomainXYZ.replit.com, which I'd ban

promptly. (Just today, I banned a bunch of links from

open-facebook.replit.app and google-official.replit.app.

How Replit isn't catching this is beyond me.) By contrast, I never saw bad

content hosted on Webflow or Squarespace, which seemed to have

much higher hurdles to usage.Trouble With More Sophisticated Criminals

With my simple domain-level whitelist/blacklist system, I had

cut down on the overwhelming majority of spam. But some of it

still managed to get through. One day, I received two emails

from Amazon and Cloudflare (which I use for hosting) that

malware had been found on my domain, and that it had been

quarantined. They had been phishing pages that only appeared as

such to users in certain geographies, e.g. if you accessed a

particular website from a USA IP, it would look like a normal

blog, but when you accessed it from a French IP, then it would

be a phishing page for the mobile phone operator Orange.

There were trickle-down consequences to this: the firms that

reported the security issue to AWS/Cloudflare had also reported

it automatically to various other anti-virus companies. Now,

some legitimate users were reporting that they couldn't access

y.gy links because they were blocked by a corporate firewall.

My next step was to up the stakes for my adversaries. Instead of

quietly deleting malicious links, I now redirected them to a

Scam Warning page.

And I figured out a trick for detecting geofenced content.

Between the two of those, abuse dropped promptly. The Scam

Warning in particular seemed effective at discouraging use,

since it warns the end-user, the recipient of the scam, that

they're being scammed, and will drive up their alertness and

distrust whatever website linked them to it.

Anecdotally, most of these cybercriminals have a "signature" in

that they only run one type of scam, the phishing pages look

similar, the URLs even look similar, etc. Once I started

forwarding their traffic to my Scam Warning page, I often saw

those signatures disappear-- probably moving on to a link

shortener that is less hostile to them and their business

models.

Toward Peace

Now that I had managed to further cut down on spam and

disincentivize it, the links that were being submitted where

overwhelmingly legitimate. I filed support tickets with various

anti-virus companies, and got y.gy unblocked. All was well. But

even with big, proprietary whitelists and blacklists, it was

still tedious to have to check manually the other links that

were getting submitted. I still had concerns:

- Even more sophisticated criminals would host legitimate content on a webpage, use that to pass the initial check, and then change it to scam content later. In order to really prevent abuse, you have to perpetually re-scan all links.

- We are just too small for a commercial link-scanning solution at scale. Something like VirusTotal costs many thousands of dollars a month.

I knew that I didn't really have great solutions to these. And I

believed that I had to have solutions to these problems, because

it would mean that otherwise I would end up running into the

same malware problems that would lead to my link shortener

getting flagged by anti-virus software. The fundamental problem

was that my API was available for free. Sure, I could require a

signup and a CAPTCHA and an email verification, but that doesn't

really deter sophisticated bad actors. Those are easy to bypass.

The big, abuse-killing hurdle is actually requiring up-front

payment. The reason why it's so effective is that payment

processors like Stripe have the most aggressive incentives for

banning abusive users. Anything that can wind up in a chargeback

is big trouble for Stripe, and that means that any users of y.gy

have already passed Stripe's aggressive fraud protection system.

That's a good horse to hitch my wagon to.

Plus, I figured I've actually built a pretty good service, so

maybe folks should be paying for it? A price as low as $4

a month is low enough that it won't deter the desirable users:

those who actually want to get value out of the service

and are using it to meet some goal, and not just incidentally.

But it will deter spammers. So, I spent a weekend paywall-gating

my APIs. Now the amount of traffic I see is a fraction of what I

saw previously -- it's actually small enough to scan

perpetually. It comfortably fits in the free- and low-cost tiers

of commercial link scanners.

Does Paywalling Cure Everything?

No, we've still seen some users pay for our service and then

upload malicious links. Whether they're using legitimately

obtained (e.g. prepaid) credit cards or stolen credit cards, we

don't know. But the way to think about all of this is like a

funnel: first they have to be willing to pay, then they have to

pass the payment processor's fraud prevention, then they have to

enter a link that doesn't get automatically caught and banned,

etc. At the end of the day, this funnel gets very thin, and it

leaves very few links that we have to run through our malware

scanners. This is now easy to manage.

Did You Leave any Free Features?

Yes, I left a free qr creator

The reason for this is that the QR code, when generated, points

directly at the destination URL, and doesn't get routed via the

Y.GY servers, so it doesn't create an opportunity to disguise a

link, and it's none of our concern. Previously we offered a QR

code creator that made Y.GY links and had all the same

customization and analytics of our short links -- but for

most folks trying to make QR codes, that stuff doesn't really

matter. They just want a QR code for their link. And we happily

provide that.

What I Learned

There was a big and important lesson here for me:

sometimes the dream of free is just too good for the practical world

I went through a lot of trouble and spent many hours before

simply killing free usage, which I should've maybe done from the

start.

This experience with a link shortener made me appreciate how

quickly and diligently cybercriminals will look for new

solutions. Because they keep getting banned everywhere else,

they will be the first users to find your new solution. And they

will try their best to exploit it -- and usually a new

project is easy to exploit because the founder hasn't done all

the anti-abuse work that mature solutions have. This means that

the hardest time for a link shortener or an email provider is on

day one.

Speaking of email providers, I had previously drafted an email

service to compete with overpriced providers like Sendgrid or

Mailgun. There's some cosmetic work that I have to do before

taking it live. Email is even more prone to abuse than link

shortening. Email costs money to send, and is the primary vector

of phishing and scams. Now that I've had this experience with a

link shortener, I know what to expect from launching an email

service. I certainly wouldn't permit any free usage, and I know

to prepare for scammers and fraudsters. I'm glad that I had this

learning experience and am not jumping first-thing into offering

a new email provider -- I would almost certainly get

overwhelmed by the problems.

On the Non-Obviousness of Software Usage

The reason why I'm writing this blog is because I had evidently

been naive about how my service would be used once I put it out

into the world. Builders of software are often naive about this;

people will use your software in ways you never even dreamed of.

By way of example of legitimate usage, when I created y.gy, I

thought it would primarily be used by marketers or engineers for

link tracking. But the reality was different: for example, I saw

tons of links from SEO farms as they were creating backlink

profiles. I was seeing tons of long links getting shortened

-- not for marketing, but just because the links were long!

I noticed quickly that I was getting a lot of international

traffic: for example, some people were shortening links to lots

of arabic-language YouTube videos. There's a group of Peruvian

newspapers that kept shortening links to all their articles.

Some folks were shortening hundreds of links to online

playlists, and I still don't know why. I didn't have any

expectations when I started this project, so that was

interesting to me!